We know Sergo Kobuladze as the great Georgian painter behind the iconic portrait of Dante Alighieri—but what if we told you he was also a photographer? And not just any photographer, but one of the first Georgian artists to experience Italy beyond the Iron Curtain, capturing the quiet charm and everyday beauty of 1950s Italy during the height of the Cold War.

It was 1956, and after more than two decades of absence, the USSR returned to the international art scene at the 18th Venice Art Biennale. This marked the beginning of what’s now known as Khrushchev’s Thaw and the so called post-Stalinist liberalization—a period of cautious cultural “openness” in an otherwise tightly controlled regime. Among the carefully selected Soviet artists, only one Georgian was sent to Italy: Sergo Kobuladze.

At the time, the Soviet Pavilion was dominated by socialist realism—heroic workers, idyllic villages, and state-approved optimism. Kobuladze quietly stood apart. He exhibited The Capture of Nestan-Darejan, an illustration from Shota Rustaveli’s The Knight in the Panther’s Skin. His work drew attention, and SELE ARTE, a respected Italian art magazine, named it one of the highlights of the exhibition.

But it wasn’t just his paintings. With a camera slung over his shoulder, Kobuladze wandered the streets of Rome, Florence, Venice, and Milan, photographing everything that caught his eye. And it really was everything—grand cathedrals, yes, but also neon signs, shop windows, stylish coats, and quiet streets at dusk. According to notes in his archive, he hardly slept—determined to take in every moment. After all, he was finally seeing the world he had studied in books and paintings come to life. These photographs, long kept in his personal archive, are now preserved at the George Chubinashvili National Research Centre. And this year, they’ve finally come to light.

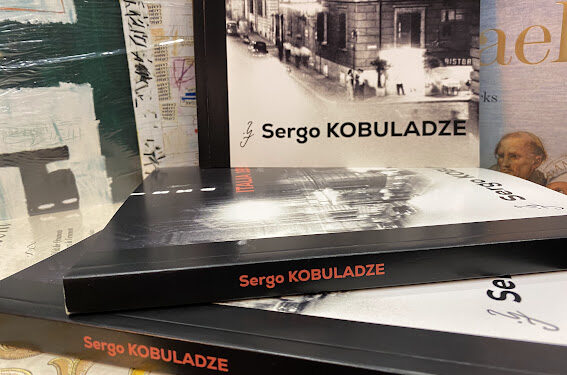

“Italy 1956: Photographer” is the first photo album to bring together these remarkable images—a visual diary of an artist experiencing the West not through ideology, but through genuine curiosity and awe. It’s a rare, poetic glimpse into the past—of a time when borders were rigid, but art still found ways to slip through.

What do you think?

Show comments / Leave a comment